Introduction to Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism and the moral status of animals form a fascinating intersection in ethical theory. Introduced in 1780 by philosopher Jeremy Bentham in his book Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, this framework emphasizes utility as the guiding principle of morality.

At its core, utilitarianism revolves around the principle of utility: actions should be judged as right or wrong based on their ability to increase happiness or reduce suffering. In simple terms, good actions promote happiness and combat suffering, while bad actions do the opposite (Rachels, 2006, p. 148).

Key Propositions of Utilitarianism

Classical utilitarianism, also known as act utilitarianism, was developed by Bentham and later expanded by John Stuart Mill. It rests on three key propositions:

- The Consequentialist Principle: Actions are judged solely based on their consequences. This is the foundation of utilitarianism—the idea that results matter more than intentions.

- Happiness as the Ultimate Goal: When evaluating the consequences of an action, the only factor that matters is the amount of happiness or unhappiness it generates. Mill articulated this by stating, “Happiness is desirable and the only thing desirable as an end; all other things are desirable only as means to that end” (Rachels, 2006, p. 164).

- Impartiality: Every individual’s happiness counts equally. Mill emphasized this egalitarian aspect by arguing that we must be “strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator” (Rachels, 2006, p. 165).

These propositions make classical utilitarianism a highly practical and inclusive ethical framework. However, as with any theory, it comes with complexities and criticisms.

Consequentialism: Strengths and Challenges

What is Consequentialism?

A cornerstone of utilitarianism is consequentialism, which asserts that the ethical value of an action depends entirely on its outcomes. This principle often puts utilitarianism at odds with deontological ethics, which emphasize rules and duties regardless of consequences.

For example:

- Deontological ethics might argue that lying is inherently wrong, even if it could save a life.

- Utilitarianism, however, evaluates whether the lie produces more happiness or reduces suffering overall. In some cases, lying may be deemed the ethically correct choice.

Flexibility and Criticisms

This flexibility allows for pragmatic solutions to complex problems, but it can also conflict with common moral intuitions. Critics argue that:

- Justifying actions like lying or harming one individual to save many risks undermining principles like honesty and fairness.

- It may feel unsettling to justify certain actions solely on outcomes.

Rule Utilitarianism: A Balanced Approach

To address these concerns, some philosophers proposed rule utilitarianism. This refinement:

- Focuses on creating and adhering to general rules that tend to produce the best outcomes.

- For example, a rule against lying could be justified if it generally promotes trust and reduces harm, even if exceptions might exist.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Rule utilitarianism strikes a balance between flexibility and consistency, but it is not without critics. Some argue:

- Rigid adherence to rules can undermine the spirit of utilitarianism, which prioritizes outcomes over processes.

- A practical middle ground involves crafting rules with built-in exceptions, such as lying to save a life.

Ultimately, whether one adheres to act or rule utilitarianism, the focus remains on maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering through thoughtful deliberation.

The Evolutionary Perspective and Its Implications for Animal Treatment

Our Place in Nature

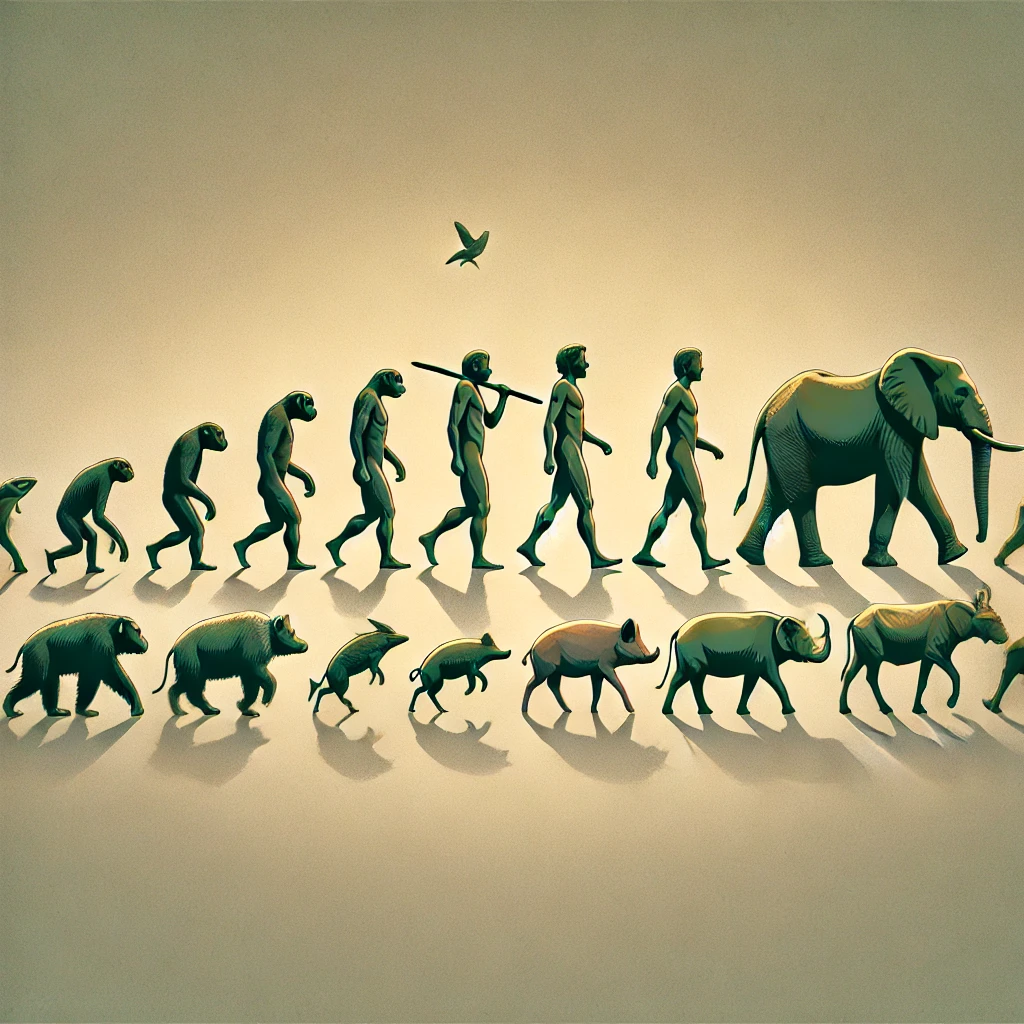

The Origin of Species, published by Charles Darwin in 1859, is perhaps the most impactful scientific work in history. The theory of evolution posits that all living beings on Earth share a common ancestor. In other words, all current species are related through descent. This is made possible by a gradual process of evolution spanning approximately 3.8 billion years, with natural selection as its basic mechanism.

Rather than delving into the detailed explanation of evolutionary theory, let us focus on its direct implications for our understanding of nature and our place within it. These implications are particularly relevant to the ethics of how we treat animals.

Challenging Human-Centric Views

Darwin’s theory of evolution challenges the traditional belief that humans are the pinnacle of creation. According to this view, humans are often regarded as being morally superior, with everything else in nature existing to serve their needs. However, evolution tells us that nature is not designed for any specific purpose or hierarchy. Instead, it is shaped by random processes and natural selection.

Ideas such as humans being “more evolved” or “closer to perfection” are false if we accept the evolutionary perspective. Evolution suggests that all species, including humans, are products of chance, not divine intent or superiority. Yet, we continue to act as if we own nature. This disconnect between our understanding of evolution and our behavior raises important ethical questions:

- Why do we persist in treating other animals as inferior?

- How should this change our actions toward nature and non-human life?

Animal advocates and environmentalists argue that these evolutionary insights demand a shift in how we view and treat animals. While evolution does not directly dictate moral rules, it undermines human-centric ideologies that have long justified the exploitation of other species.

The Role of Science in Ethics

Philosopher David Hume famously warned against deriving moral conclusions solely from factual premises—a concept known as the “is-ought” problem or Hume’s Guillotine. In simpler terms, Hume argued that you cannot jump from describing how the world is to stating how it ought to be without introducing a moral premise. For example, just because nature is competitive does not mean humans ought to act selfishly.

However, this does not mean science has no role in ethics. On the contrary, science provides essential insights for ethical reasoning by:

- Understanding Reality: Science helps us understand the world, our nature, and the consequences of our actions. For instance, ecological studies reveal the impact of pollution on ecosystems, which can inform ethical guidelines.

- Challenging Beliefs: It allows us to question outdated or false moral assumptions, such as those rooted in religious dogma. For example, if science shows that animals feel pain and have emotional capacities, this challenges traditional views that disregard animal suffering.

- Inspiring Objectivity: Ethical theories grounded in facts—like the ecological impact of polluting rivers—are more realistic and applicable than those based on superstition or unfounded beliefs.

By integrating scientific knowledge, ethics can move beyond rigid ideologies to develop fair, evidence-based frameworks. While science cannot tell us what is morally right or wrong on its own, it provides the critical information needed to make informed moral decisions. For example, if we know that animals experience suffering and possess cognitive abilities similar to humans, any ethical system must take this into account when considering their treatment.

Questioning Human Dignity

Another key challenge posed by evolutionary theory is the idea of human dignity. Many traditional ethical systems are built on the belief that humans hold a special moral status—either because they were created in the image of God or because they are uniquely rational beings. However, Darwin’s theory undermines these assumptions.

- The Image of God: Evolution shows that humans are not designed by an intelligent creator but are products of natural processes. This directly refutes the idea that humans hold a special place in creation because of divine intent.

- Rationality: While humans possess advanced cognitive abilities, Darwin argued that the difference between human and animal intelligence is one of degree, not kind. For example, many animals demonstrate problem-solving skills, social behavior, and emotional complexity. A healthy adult dog may be more cognitively capable than a human infant or an individual with severe mental disabilities.

This perspective challenges the belief that rationality is exclusive to humans and calls for a more nuanced understanding of moral worth. If we accept that intelligence exists on a continuum across species, the traditional foundation of human moral superiority begins to crumble. Ethical systems must then seek new justifications for their principles, particularly regarding our treatment of non-human animals.

The Capacity to Suffer

As discussed earlier, for utilitarianism, cognitive abilities are not the key factor in determining whether an individual deserves moral consideration. Instead, the critical factor is the capacity to feel pain and suffer. Jeremy Bentham expressed this succinctly:

“The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

This fundamental question underpins the utilitarian approach. Most people acknowledge that animals can suffer—anyone who has accidentally stepped on a cat’s tail or witnessed a dog in pain can attest to this. However, some skeptics still argue that animals may not experience suffering as humans do. They suggest that animals might be “Cartesian automatons,” responding mechanically to stimuli without conscious awareness.

Yet this view is inconsistent with both scientific evidence and common sense. When humans experience pain, they cry out, recoil, and try to escape the source of discomfort—animals exhibit the same behaviors. Furthermore, animals, like humans, possess complex nervous systems that process pain signals. The only difference is that humans can verbalize their suffering, whereas animals cannot. Importantly, even humans who cannot communicate—such as infants or individuals with severe disabilities—are still recognized as capable of suffering.

Scientific studies, particularly those involving laboratory animals, demonstrate that animals respond to painful stimuli in ways that closely mirror human reactions. Paradoxically, while some people deny that animals can suffer, much of modern medicine relies on animal testing, which implicitly assumes that their reactions to pain are similar to ours.

If animals can suffer, utilitarian ethics demands that we include their suffering in our moral deliberations and treat it with the same importance as human suffering. However, this raises practical questions: How do we align this ethical principle with practices like factory farming or animal testing? Addressing these issues requires examining the responsibilities and opportunities we have to live in accordance with our moral obligations toward animals.

The Moral Status of Animals

The capacity to suffer is sufficient to grant a being moral status, meaning their interests must be considered in our ethical decisions. But does this mean all animals capable of suffering have the same moral status? Is the life of a human, a dog, and a mouse equally valuable?

Consciousness and Self-Awareness

Many philosophers argue that humans are not only conscious but also self-aware. Self-awareness is defined as the ability of an individual to see themselves as a distinct entity with a past and future. This capacity has often been seen as a requirement for personhood, which some claim grants humans moral superiority over other beings.

However, this distinction between beings with and without self-awareness does not align neatly with species boundaries. For example, young children and individuals with severe cognitive impairments are not self-aware in the same way as healthy adults, yet they are still considered members of the human species. At the same time, research shows that some animals—such as great apes, dolphins, elephants, and certain birds—exhibit behaviors indicating self-awareness. They pass tests like mirror recognition and demonstrate the ability to anticipate future needs.

Even species with less obvious markers of self-awareness, such as dogs, show behaviors that suggest they perceive themselves as distinct entities in time. Only those who have spent little time with animals—or hold strong biases against them—would argue otherwise. Philosophical and empirical studies challenge the notion that self-awareness is uniquely human, calling for a reassessment of moral status across species boundaries.

Life in a Biographical Sense

Philosopher R. M. Hare argued that self-awareness alone is not sufficient to grant a being the status of personhood. According to Hare, a person must also possess a “biographical life”—the ability to narrate stories about their past, evaluate their life as a whole, and plan for the future. This perspective often ties biographical life to linguistic abilities, which are considered necessary for creating narratives about one’s existence.

Individuals who are self-aware but lack a biographical life are sometimes referred to as “near-persons.” These beings lack the cognitive capacity for complex storytelling, yet they may still exhibit self-awareness and consciousness. For example, many animals demonstrate self-awareness and the ability to remember past events and anticipate future outcomes, even if they cannot express this linguistically. Elephants, dolphins, and some birds exhibit behaviors that suggest a sense of continuity in their lives.

This raises critical ethical questions: Should the inability to articulate a biographical narrative diminish the moral status of a being? Or should moral consideration extend to those who, despite lacking language, clearly exhibit rich inner lives?

The Continuum of Suffering and Consciousness

As previously discussed, attributes like rationality, consciousness, self-awareness, and biographical life exist along a continuum rather than being absolute distinctions. This perspective aligns with the evolutionary understanding that traits develop and vary among individuals and species.

For example, vertebrates share a central nervous system, a characteristic inherited from a common ancestor. This suggests that all vertebrates likely experience pain, albeit to varying degrees. While a dog or pig might experience suffering more similarly to humans, other animals like salamanders may experience pain differently due to their simpler nervous systems. For invertebrates like octopuses or crustaceans, scientific evidence increasingly supports the view that they too can experience pain, though their suffering may differ from that of vertebrates.

Recognizing this continuum allows us to make more informed and compassionate ethical decisions. Acknowledging that a pig’s ability to suffer may be comparable to that of a human infant underscores the need to consider their suffering with equal seriousness. At the same time, it challenges us to reassess how we value the lives of animals versus humans, moving beyond species-based biases.

Similarly, consciousness and self-awareness also exist along a continuum. While many humans possess a high degree of biographical life, some do not—such as infants or individuals in comas. Conversely, some animals like elephants, apes, and dolphins exhibit remarkable levels of self-awareness, further blurring the lines traditionally drawn between humans and other species. This understanding encourages a more nuanced and inclusive ethical approach, grounded in the individual capacities of beings rather than arbitrary species distinctions.

Hedonism and Preferences

We have explained distinctions made by many philosophers between persons, near-persons, and merely conscious beings. These distinctions influence how we value the lives of beings and when it may be justifiable to take a life. Preference utilitarianism, a branch of utilitarian thought, argues that our moral obligation is not to maximize happiness and minimize suffering, but rather to satisfy the preferences of those affected by our actions.

For instance, the preference of a person with a biographical life to continue living may be stronger than that of a near-person (e.g., a dog) or a merely conscious being (e.g., a shrimp). Therefore, all else being equal, it would be morally worse to take the life of the person with a biographical life.

However, this perspective has its limitations. Preference utilitarianism tends to subordinate suffering and pleasure to preferences, which can lead to problematic conclusions. For example, the value of pain or pleasure is, in our view, independent of preferences. The utilitarianism we defend retains its hedonistic foundation: there is no greater evil than causing suffering and no greater good than promoting well-being (Singer, 2011, p. 117).

Balancing Preferences and Suffering

While preferences play an important role in determining the value of life, they must be contextualized within the framework of suffering and consciousness. For example, if an adult dog’s capacity to project its life into the future is equivalent to that of a two-year-old child, it is reasonable to assume their preferences to avoid death are equally strong. Consequently, killing an adult dog may be as morally wrong as killing a young child, all else being equal.

Nevertheless, the moral relevance of the capacity to suffer surpasses considerations of life’s value. If two beings share the same capacity to suffer, other characteristics—such as self-awareness or biographical life—become secondary. For example, the suffering of a cat being tortured is no less significant than that of an adult human enduring the same pain. Both deserve equal consideration.

This hedonistic focus does not negate the importance of preferences but highlights that alleviating suffering and promoting well-being should remain our highest ethical priorities. By doing so, we can create a framework for ethical decision-making that is inclusive, compassionate, and grounded in the realities of sentient experience.

Conclusion

Utilitarianism offers a powerful ethical framework that emphasizes the importance of happiness and the reduction of suffering for all sentient beings, regardless of species. By focusing on the capacity to suffer, rather than arbitrary distinctions like species or intelligence, this philosophy challenges us to extend moral consideration to animals and rethink long-standing practices that cause unnecessary harm.

Through the lens of evolution, utilitarianism further dismantles human-centric views, reminding us that humans are not separate from nature but part of a continuum shared with all living beings. This perspective encourages us to reconsider our role in the world and the impact of our actions on animals and the environment.

Ultimately, utilitarianism asks us to approach moral questions with empathy, impartiality, and a commitment to maximizing well-being for all. In doing so, it paves the way for more compassionate and equitable relationships with the animals who share our planet.

Bibliography

Recommended Reads: Some of the links in this section are affiliate links. If you purchase a book through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. This helps support the blog and allows me to continue creating content. Thank you for your support!